[ad_1]

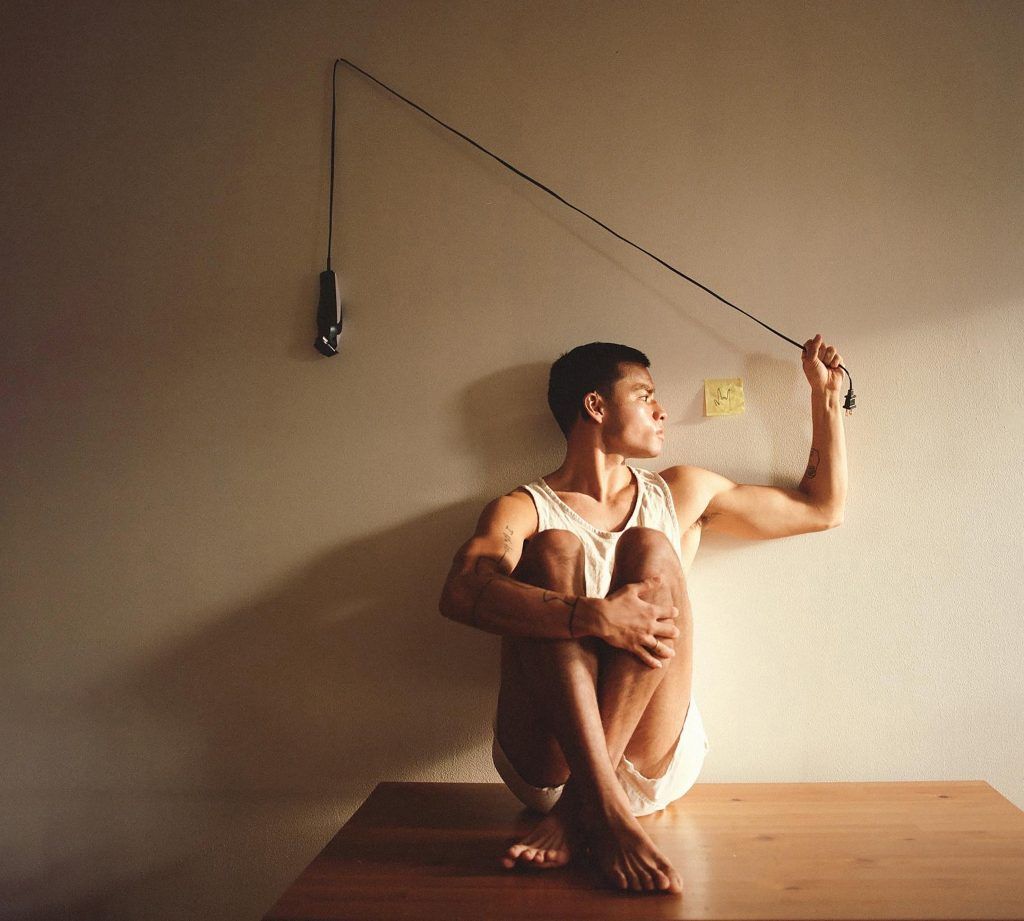

Actor, model, artist, author and LGBTQIA+ activist CHELLA MAN tells GENNADY ORESHKIN about using art to heal and creating space for himself, both literally and figuratively

“If I had been born during any other era, my story would be different. The world would not be ready to understand with open hearts and minds. To this day, many still choose not to. But whether they choose ignorance or empathy is up to them. My story will still be here; it will never be erased.”

My first “encounter” with Asian-American actor, model, artist and LGBTQIA+ activist Chella Man was in 2018, watching his “Becoming Him” TED x Ranney School talk on YouTube. The then-19-year-old displayed greater empathy and discernment than any of my contemporaries in their twenties. Man spoke about coming to terms with his identity as a genderqueer trans man of colour. Then last year, he wrote Continuum, which went even deeper into the process of his painstaking growth and navigating the world as a deaf person. “To become the man I am today, I had to make several realisations,” he said, one of them being the difference between presentation and identification.

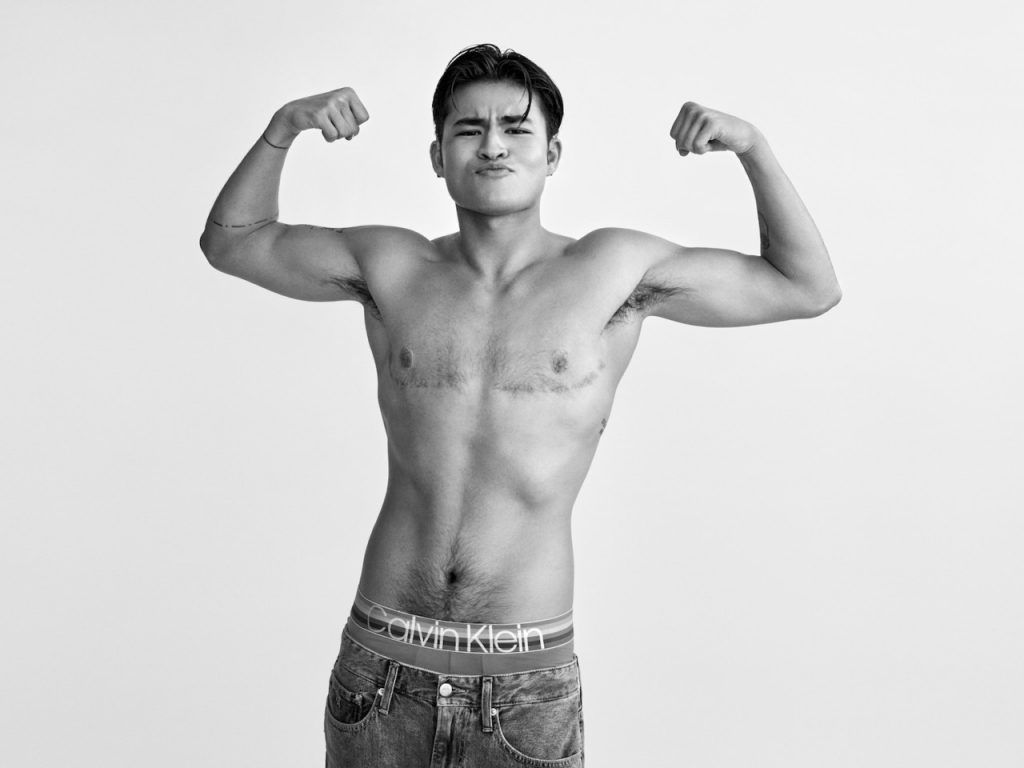

And breaking a bunch of barriers along the way, Man, who became the first trans-masculine model signed by IMG in 2018, and has helmed campaigns for Calvin Klein, Gap, American Eagle and Saint Laurent, and a year later rose to prominence as the mute superhero Jericho in the TV series Titans, last month took to Instagram to announce a new partnership with Nike. “I’ve been speaking with them about disability and had a bunch of different ideas of ways that sport, movement and Nike could prioritise accessibility and inclusivity,” he explains. The collaboration came to fruition as a part of the sportswear giant’s BeTrue campaign, which aimed to create safe spaces for the members of marginalised communities, where they can “explore what makes their body, heart, and mind feel at rest and peace”.

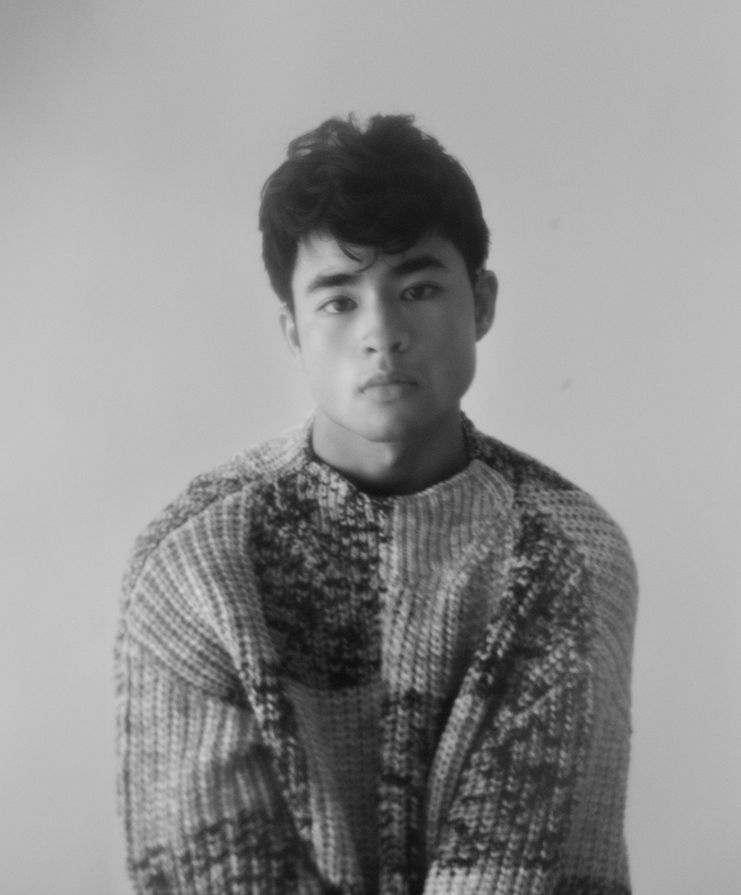

Continuum struck me with its raw emotionality – he earnestly documents his experience, bereft of sensationalism and free of synthetic plot devices that manipulate readers into empathy. “To be quite honest, I didn’t have anyone around me growing up in central Pennsylvania – a very conservative town that didn’t mirror who I was. I identify as trans, deaf, Jewish and Chinese, and there was no guidance for that,” he tells me. With an open heart, Man confesses his encounters with the cruelties of the world – being misunderstood, frustrated, gaslit. “I was feeling all of these heavy, drastic emotions, yet there was nothing around me that could really [validate them],” he recalls. “Now, I realise it’s largely due to systemic oppression and the cycles of discrimination that I was experiencing, dealing with racism, transphobia and ableism…”

“Being his own representation,” as it turned out, was sine qua non in a media landscape where, until very recently, the only mainstream portrayal of trans people was either caricatural or tragic for tragedy’s sake – outsourced to white, cishet people (think, Dallas Buyers Club (2013), and the “brilliant”-in-its-ignorance mess The Danish Girl (2015).

Intersectionality wouldn’t hit the screens of wider audiences until Ryan Murphy’s award-winning television series Pose (2018-21), which combined New York’s drag-ball culture, LGBTQ subculture, and the African- American and Latino communities. “I didn’t see a framework or guidance on how to navigate a world that didn’t accommodate a body like mine in the way that I perceive and receive sound, in the way that I don’t succumb to the gender binary or pass as white,” explains Man. “This has been the biggest art project of my life.”

He elaborates on how the lack of a framework has moved him towards designing his own path and tools, which was possible, in many ways, by meeting and interacting with queer, BIPOC (black, indigenous and people of colour) and disabled communities around the world. Now, trans, disabled youth have at least one piece of mainstream representation in the face of Titans’ Jericho.

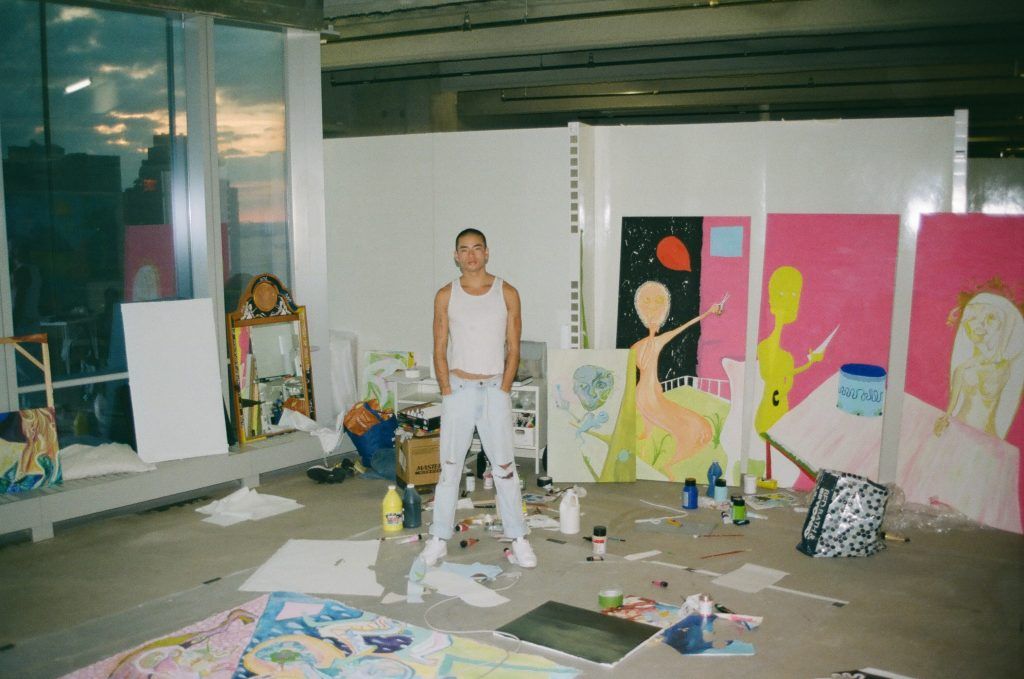

Man’s art defines a niche of its own. His compositions bear likeness to those of George Condo, but with the soft, finer and smoother lines of Dalí. Much of his work is profoundly introspective, “A lot of my work deals with what other people believe to be a vulnerability,” he says. “I feel more connected to the artwork that displays honest emotion, perspective and revelations, but it’s not necessary. I don’t think art is definable.”

And what about its potential to heal? “[Art] allows emotions to move through my body and be translated into external pieces without me holding them inside until I combust. It also allows me to express myself when I don’t have the language or terminology to do so,” Man explains. “What’s so beautiful about art is there’s no specific way anything has to be, and that’s how my existence has been.” In 2021, Man shot a short film titled The Beauty of Being Deaf, in which he featured friends who found themselves under the BIPOC-and-deaf umbrella.

Man’s latest curatorial venture, the Pure Joy exhibition at Lower Manhattan’s Gallery 1969, brought together 14 disabled visual and performance artists of different ages, races and stages of their careers.

“The media range from sculpture, live performance, art drawing, painting and video portraiture, to furniture, fabrication and found objects on display,” he explains. “I wanted there to be such a range because I feel disability is expansive. I wanted the flavours of the artists involved and their choices of medium to mirror that.” Man then elaborates on the exhibition’s theme, “Some people chose to make work directly about the title, so it centres the literary tone of the word, happiness, and joy, [while] others create work about pain and suffering with their disability. The joy in their work [becomes] the process of the creation itself, rather than a stereotypical definition of happiness and joy.”

One of the participants Man approached was Christine Sun Kim, a Berlin-based American visual, performance and sound artist. Man came across Sun Kim, interestingly, while watching her TEDTalk six years ago. “I was blown away to find someone who was deaf, Asian and a woman – which I was identifying as at the time, [since] I didn’t know there was any other [way],” he says. “I’ve looked up to her work for years, admired from afar and have been cheering her on. Then we met – I think I went to see her speak at the Whitney.”

Man is currently enrolled in a VR programme at The New School in Manhattan, a degree choice that seems far from incidental. “Most people don’t think outside their experiences unless they’re prompted to. What if all it took is for someone to put on a VR headset and [emerge in] a simulation where they could experience what we [go through]?” The experiences that might, to a cis, able-bodied individual seem ordinary, often adopt certain specificities for people beyond such spectrum. Man enlists the help of a scenario with a metaphysical burrito to illustrate the point, “…going to order a burrito as a deaf individual and having to explain and advocate for your deaf identity, and ask them to write things down”. Not to mention navigating the bathrooms as “someone who doesn’t pass as cis. Not only would that evoke compassion and empathy, but it would just allow for perspective,” he adds.

So how does he approach the work he does for the likes of Saint Laurent and Gap? “I see modelling as a form of performance art,” he says, “Depending on the job at hand, you have to mould your body into [a specific vibe].” The tales of the modelling industry triggering body dysmorphia know no end, thanks, sometimes, to the runway equivalent of stage moms à la Yolanda Hadid. “To this day, even after gender-affirming care (top surgery and taking testosterone), I still feel there are days that I oscillate with how much I connect to my body,” Man adds. “I believe that modelling has allowed me to connect to my body more because I’ve had to be aware of it, but it also definitely emphasised the Eurocentric beauty standards.” To him, one of the takeaways of such work is letting go of “what your image looks like”, because models are only in (some version of) control when they’re on set.

Man began his transition in 2017. In “Becoming Him”, he goes on to acknowledge his privilege of being able to receive masculinising hormone therapy. “Hi, my name is Chella Man, and this is my voice 34 weeks on T,” the montage at the end of his TED Talk says – aside from his voice getting deeper and raspier, his face was emitting new quanta of unadulterated joy with every week passing. And, while we have a long way to go to reach universal acceptance of the underrepresented, be it identity, status or bodies-specific, there’s solace in perspective.

“Look at how far we’ve come in the past five years. If I were alive at any other time period in the world, I don’t think I’d be here in the same way. I don’t think I’d be doing this interview. I don’t think I’d be able to curate this gallery show. So I believe hope will prevail essentially and we will prevail.”

And so the manifestations of Chella are still work in progress. Some journey.

[ad_2]

Source link